Before email and social media, the best way to reach across the miles to share a brief, friendly greeting was the picture postcard. From the 1890s through the 1910s, the US, Great Britain, and Europe saw the Golden Era of the “postcard craze.” Over this twenty-year period, explains collector and author Salo Aizenberg, at least 200 billion cards were sold. Only the telephone could stop the craze in the post-WWI years. Germans were the undisputed industry leaders, supplying postcards of high quality, featuring colored images unavailable in photographs around the world. Every subject imaginable appeared, from scenic locales to classic art and from holiday greetings to nudity. This window to the world, however, was also replete with racism and xenophobia, including anti-Black, anti-Asian, and antisemitic imagery and tropes. We may think of the rise of the Nazi party as bringing antisemitism to Europe, but, in truth, the history of picture postcards reveals a chronicle of popular hatred of Jews beginning many decades before the Holocaust.

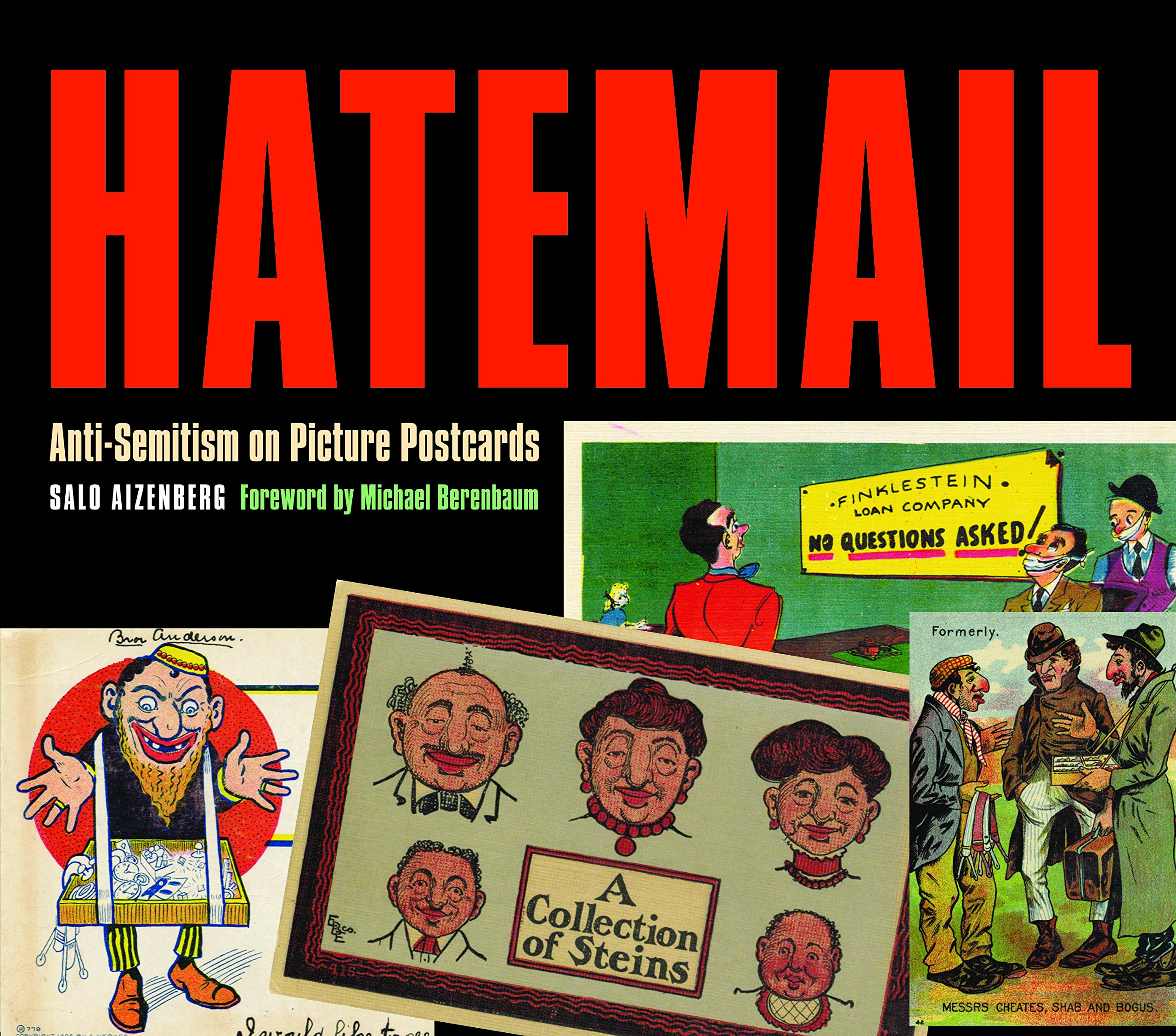

Hatemail is a vivid, detailed introduction to the subject of postcards and their connection to antisemitism. This thick, coffee-table style paperback includes over 250 images from the author’s collection, in numerous short, informative chapters that build a powerful portrait. The book begins with a guiding Introduction, including discussion of the origins of the postcard and the history of antisemitism (on and off postcards). Chapter 1 follows with the history of the Dreyfus Affair (involving the wrongful, antisemitic arrest in 1894 of French Jewish military officer Captain Alfred Dreyfus for espionage). We learn how the public clash of perspectives, including reactionary support for Dreyfus’s prosecution as well as political outcry against it, emerged in multiple series of postcards. Aizenberg takes the reader carefully through these examples that in many ways show the origin of the antisemitic postcard before moving on to the Golden Era of anti-Jewish images that emerged thereafter.

Chapter 2 provides an overview of the primary stereotypes and myths to be found on postcards during their height of popularity, with each trope lavishly illustrated in large color photos from the author’s collection. We witness examples of the large, hooked nose; wealth, greed, and cheating; the awkward, deformed body; Jews as animals; expulsion and exclusion; Jews in power; mockery of beliefs (i.e. ridicule of prohibitions against eating pork); and Jews as unsuitable for the military.

Following this overview is a chapter devoted to Germany. As Aizenberg explains, while France and the Dreyfus Affair may have introduced the antisemitic postcard to a worldwide audience, Germany published the most diverse and virulent cards in the highest quantities. The peak era for the German antisemitic postcard dovetailed with the general Golden Era. On display and deeply troubling are the cruelty, crudeness, and grotesqueness of the cards, their ”humor” and social commentary blending in breadth and offensiveness. Here and throughout this volume of 200+ pages, we learn as we view, for Aizenberg includes translations and ample discussion of each postcard presented, explaining content, production information, and social/historical context.

Chapters four through seven next bring us short but potent considerations of antisemitic postcards from France, Great Britain, the United States, and “other nations” (including Poland, Hungary, and French North Africa). We are invited to compare artistic styles, tone, and content from these varied locations, witnessing both similarities and particularities linked to differing cultural attitudes and experiences.

Three additional short chapters add focus on “The Little Cohn,” an antisemitic song that produced its own series of cards; on cards produced for tourists to the (then) Austro-Hungarian tourist spa towns of Karlsbad and Marienbad; and on Nazi-era postcards. I found the first two focuses particularly compelling, as I knew nothing about either subject. The Nazi focus was the most familiar to me, including some famous images that also appeared during the era on posters and flyers – and today on some contemporary neo-Nazi websites.

The book concludes with a focus on anti-Israel postcards, highlighting antisemitism in images that attack Israeli politics, mostly from a Muslim perspective. Readers should note that Aizenberg writes from a strongly pro-Zionist perspective (here and in the introduction) that generalizes about Islam and is necessarily limited in conclusions by its publication a decade ago.

Reading and considering the wealth of images in this engaging book brought me ample food for thought. The combination of its coffee table size and style alongside its troubling material offers a jarring, potent experience. Hatemail offers us an important opportunity to consider today’s antisemitic memes and tweets in light of past popular discourse, to see just how much – and how little – has changed.

Author bio: Elyce Rae Helford, PhD, is a professor of English and director of the Jewish and Holocaust Studies minor at Middle Tennessee State University. Her most recent book is What Price Hollywood?: Gender and Sex in the Films of George Cukor. Reach her at elyce.helford@mtsu.edu.

0Comments

Add CommentPlease login to leave a comment